Grandmothers should be wise. It’s one of those archetypal attributes of the crone, isn’t it? So when I fall short in the wisdom department, it bothers me.

A little over a year ago, my grandson and I were chatting about the first house he lived in – a place he dimly remembered, having moved away when he was a toddler. His younger sister was confused. She insisted they had never lived in a house with two huge trees in the garden. When her brother pointed out that this was before she was born, she became almost hysterical.

“But where was ME?” she demanded, her eyes filling with tears and panic.

“But where was ME?” she demanded, her eyes filling with tears and panic.

That was when I fell short in the wise grandmother stakes. I knew my answer to the question, but I would have struggled – when put on the spot – to find the words to explain it to a tiny child. Even if I had managed to leap that hurdle, I was anxious about straying into the sphere of beliefs. I’ve spent a lifetime as a teacher carefully and meticulously respecting a wealth of different creeds and cultures. I knew my grandchildren were being brought up with a nominally Christian belief system. Christianity has plenty to say about an afterlife, but is curiously silent on before life. It talks vaguely about dust and ashes, which, I felt, wouldn’t help much. Did I have the right to impose my own beliefs on those they were being brought up with?

So I failed. I gave the child lots of comforting cuddles, chatted to her about how excited we’d all been when she was born, and generally distracted her without ever answering her very important question. And it has bothered me ever since.

When I came to write my children’s novel this year, I decided it would give me the opportunity to revisit the events of that day and to provide Ruby Rose, my fictional toddler heroine, with a fearless crone figure who is more than happy to address her question head on and provide a suitable response.

It was one of those parts of the book that quite happily wrote itself, while I obediently pressed the keys. Interestingly, Misty often took control of me, as well as the situations in the story, when she appeared in the pages!

Misty waited for the girl to settle down and for the pounding of her heart to slow. “Now,” she began, finally. “That was a very sensible question you asked, my dear. I’m going to answer it for you, but you will need to listen very hard. Can you do that?”

Ruby nodded miserably and Stellan sat on the grass at Misty’s feet, because it had never occurred to him that there could be an answer to that question.

“Before you were your mama’s little girl and Stellan’s little sister, Ruby, you were living in the Dreaming Place.”

“What’s the Dreaming Place?” Ruby asked, sitting up.

“It’s a place you know very well. Why, you go there every night, while your body is in bed, having a rest,” Misty replied.

“You mean when we have dreams?” asked Stellan.

“Exactly. Haven’t you ever thought how odd it is that your body stays in bed, fast asleep, while you are off doing all sorts of other things?” …

“That is strange,” agreed Stellan, who had never really considered it before.

“So,” continued Misty, in the same calm, gentle voice, “while we have bodies like these,” she tickled Ruby Rose gently on her arm and the child giggled, “we live in them for most of the time and just put them down to rest at bedtime. Before we are born, though, and after we have died, we spend all our time in the Dreaming Place. That’s where you were when Stellan was a little boy and Bella the cat lived with him.”

Both children were silent for a moment, while they considered that.

“Weren’t I lonely without my ma and my pa and my brother?” Ruby wanted to know.

“Not at all,” Misty replied. “You were having too much fun! You see in the Dreaming Place, you can be whatever you want and go anywhere you like. You might have tried being a fairy or a brave explorer or even a dog or a cat. What do you think you would have been?”

“A fairy who could fly in the air and do wishes!” Ruby announced.

“Well that would be quite splendid, wouldn’t it?” Misty smiled. “But after loads and loads of dreaming, you decided that what would be even more fun would be to become a little girl with a body. You see, in the Dreaming Place there are things we can’t do. We can’t feel happiness or pain or full up with delicious food or the softness of an animal’s fur when we stroke it. You decided to find yourself the most perfect family for your new body to live with.”

“How did she find us?” asked Stellan.

He couldn’t decide whether this was some kind of made-up tale to calm his sister and cheer her up or whether Misty believed all she was saying.

She smiled at him. It was a serious smile, not the sort of winking smile grown-ups give when you and they both know they are pretending.

“As I said, in the Dreaming Place, you can go anywhere you want just by thinking about it. Once Ruby Rose had decided she wanted to slip into a body and find a family in this – Waking Place, she travelled all around the world, deciding which would be the very best family for her to live with. Eventually, she chose the family she wanted and when your new little sister was born, here she was!”

“I was very clever to choose my nice family, weren’t I, Misty?” Ruby smiled.

My grandson is reading The Glassmaker’s Children at the moment and maybe, when she’s a few years older, his sister will do the same and find a belated answer to her question.

That from the artist who also claimed that it took him four years to learn to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to learn to paint like a child. It’s a perspective that interests me.

That from the artist who also claimed that it took him four years to learn to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to learn to paint like a child. It’s a perspective that interests me. And what of magic? I would argue that this, too, is something a small child experiences and responds to in a very natural, comfortable way and trying to regain that instinctive connection to the magic inherent in their lives takes many years, once the child has been trained to put it aside.

And what of magic? I would argue that this, too, is something a small child experiences and responds to in a very natural, comfortable way and trying to regain that instinctive connection to the magic inherent in their lives takes many years, once the child has been trained to put it aside. As a parent and as a teacher, I ended every day with a story. It felt the right way to finish things off and send my own children off to their dreams or my pupils off to their homes.

As a parent and as a teacher, I ended every day with a story. It felt the right way to finish things off and send my own children off to their dreams or my pupils off to their homes. Perhaps my favourite – if I had to choose one – though, is not an ‘issues’ book series at all but a set of comedy tales called The Bagthorpe Saga by the brilliant Helen Cresswell.

Perhaps my favourite – if I had to choose one – though, is not an ‘issues’ book series at all but a set of comedy tales called The Bagthorpe Saga by the brilliant Helen Cresswell. I went to my still fairly extensive children’s book collection (who can throw books away?) looking for stories that would interest a 5 year old and her 8 year old brother. Almost at once my eyes fell upon Hugh Lipton and Niamh Sharkey’s beautiful

I went to my still fairly extensive children’s book collection (who can throw books away?) looking for stories that would interest a 5 year old and her 8 year old brother. Almost at once my eyes fell upon Hugh Lipton and Niamh Sharkey’s beautiful  I wish life was like that for real children. I wish there hadn’t been so many children in my life who had parents consumed by addictions, parents who turned to crime, parents who ran off to enjoy a new, carefree life without the drudgery of parenthood. I wish two of those children hadn’t been my own grandchildren.

I wish life was like that for real children. I wish there hadn’t been so many children in my life who had parents consumed by addictions, parents who turned to crime, parents who ran off to enjoy a new, carefree life without the drudgery of parenthood. I wish two of those children hadn’t been my own grandchildren. For a start, I hadn’t applied to join any such group. For an end, he quickly moved into an unabashed sales patter, telling me that in order to get top price ticket sales at my talks, I needed to enrol on his training course, which would maximise my earnings.

For a start, I hadn’t applied to join any such group. For an end, he quickly moved into an unabashed sales patter, telling me that in order to get top price ticket sales at my talks, I needed to enrol on his training course, which would maximise my earnings. I spend vast amounts of time making 1/12 scale miniature figures and room settings by upcycling mass produced and junk items. It’s a brilliant hobby for me. I can be creative, inventive and gloriously messy. It involves constant problem-solving that keeps my mind active.

I spend vast amounts of time making 1/12 scale miniature figures and room settings by upcycling mass produced and junk items. It’s a brilliant hobby for me. I can be creative, inventive and gloriously messy. It involves constant problem-solving that keeps my mind active. People say, “You must have such patience,” but for me it’s a kind of meditation. I do my deepest meditating when I’m hand-stitching a minuscule white shirt or sticking tiny tufts of hair on to a wig base.

People say, “You must have such patience,” but for me it’s a kind of meditation. I do my deepest meditating when I’m hand-stitching a minuscule white shirt or sticking tiny tufts of hair on to a wig base. I was woken this morning – as I am almost every day – by Caw. And I knew, suddenly, that the Book of Caw needs to be written. Maybe by me, maybe by someone else. Who can say? All I know is that the image of The Book of Caw is lodged in my mind now and the only thing that will move it on is for me to start writing.

I was woken this morning – as I am almost every day – by Caw. And I knew, suddenly, that the Book of Caw needs to be written. Maybe by me, maybe by someone else. Who can say? All I know is that the image of The Book of Caw is lodged in my mind now and the only thing that will move it on is for me to start writing. Let’s stop metafizzing, briefly, and bring Caw into our familiar material world. As I said at the start, Caw wakes me each morning. It is the sound of the corvids – the rooks and jackdaws and magpies that restlessly circle my cottage, squawking to one another, playing some complex aerial game of tag and scattering black feathers in my garden. I won’t even begin to delve into the folklore that surrounds this family of birds, but it’s found all around the world. They are mysterious, intelligent, cunning and wise. Certainly not light and fluffy. They have a gravitas that commands attention and respect, verging on fear at times. Caw is all that.

Let’s stop metafizzing, briefly, and bring Caw into our familiar material world. As I said at the start, Caw wakes me each morning. It is the sound of the corvids – the rooks and jackdaws and magpies that restlessly circle my cottage, squawking to one another, playing some complex aerial game of tag and scattering black feathers in my garden. I won’t even begin to delve into the folklore that surrounds this family of birds, but it’s found all around the world. They are mysterious, intelligent, cunning and wise. Certainly not light and fluffy. They have a gravitas that commands attention and respect, verging on fear at times. Caw is all that. Caw is the rook on the chessboard, too. Sometimes hiding in the corner, biding its time; sometimes castling – not afraid to reveal itself in order to protect what is of the most value. Then, when the time is right, striking suddenly – covering vast distances in a dead straight line to get to the core of the action. Caw is that too.

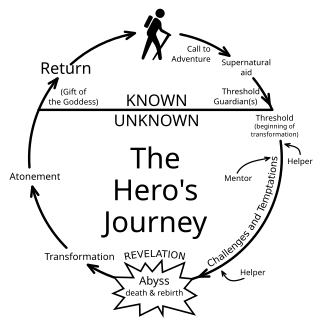

Caw is the rook on the chessboard, too. Sometimes hiding in the corner, biding its time; sometimes castling – not afraid to reveal itself in order to protect what is of the most value. Then, when the time is right, striking suddenly – covering vast distances in a dead straight line to get to the core of the action. Caw is that too. I’ve had this theory, for quite a long time now, that my life is based around a fairy tale… and just maybe everyone’s is.

I’ve had this theory, for quite a long time now, that my life is based around a fairy tale… and just maybe everyone’s is.